It is November 10, 1975. The United Nations General Assembly just passed Resolution 3379, which declared that “Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination.” Many countries we might expect, from Australia to the United Kingdom to the United States, voted against the infamous resolution. Some countries abstained from voting. Those voting in favor included the Soviet Union, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Iran, among many others.

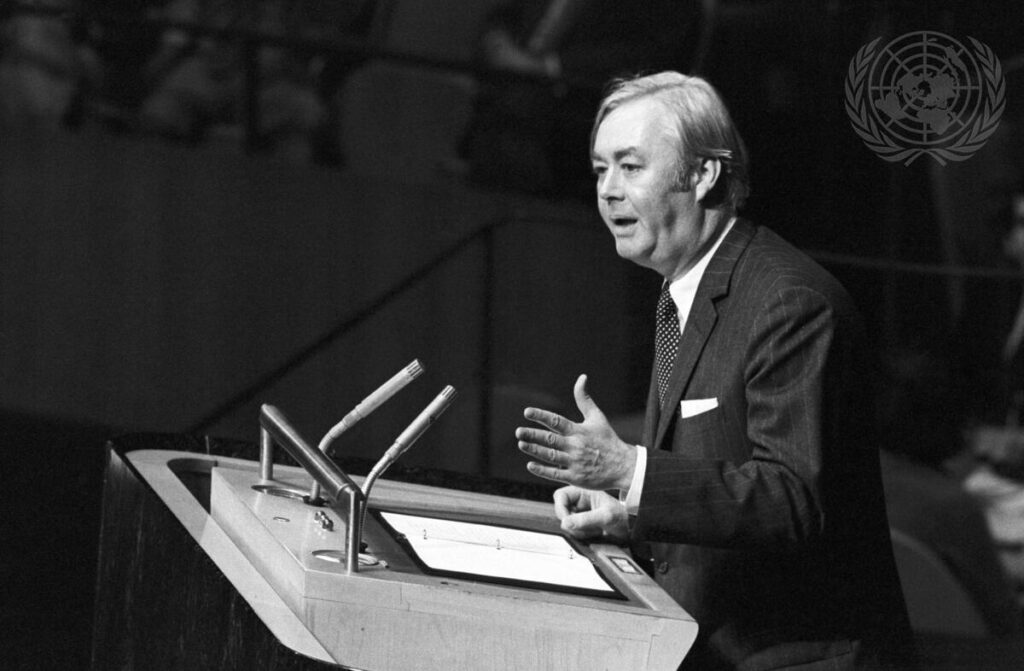

The United States Ambassador to the UN at the time, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, approaches the podium to deliver a rebuke of this resolution: “the United States rises to declare before the General Assembly of the United Nations, and before the world, that it does not acknowledge, it will not abide by, it will never acquiesce in this infamous act.”

Moynihan called the notion of Zionism being tied to racism a “terrible lie,” never mind that the UN declared this “without ever having defined racism.” Moynihan does clarify that the international body has indeed defined “racial discrimination,” but not racism, which he describes as a “doctrine” and “incomparably” a “more serious charge” compared to the practice of racial discrimination.

As a reference point, Moynihan directs listeners to the definition of racism provided by Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, which involves “a belief in the inherent superiority of a particular race and its right to dominate over others.” According to this definition, racism, Moynihan asserts, “has always been altogether alien to the political and religious movement known as Zionism.”

Zionism, he argues, “defined its members not in terms of birth, but of belief,” and considers “Jewish anyone born of a Jewish mother or — and this is the absolutely crucial fact — anyone who converted to Judaism.” Indeed, “there are many Jews who are converts” on top of a significant population of non-Jews living in Israel. Moynihan even went so far as to say that Israel “could not become racist unless it ceased to be Zionist.”

Finally, he states that definitions matter: “how will the people of the world feel about racism and the need to struggle against it, when they are told that it is an idea as broad as to include the Jewish national liberation movement?” Similarly, Moynihan observes, words like “national self-determination” and “national honor” will suffer a similar fate. So, when “the small nations” need to defend themselves, “on what grounds will others be moved to defend and protect them, when the language of human rights…is no longer believed and no longer has a power of its own?”

While Moynihan, who was born into an Irish Catholic family, was not Jewish, historian Gil Troy explains in his book Moynihan’s Moment that Moynihan understood the resolution as “a totalitarian assault against democracy itself, motivated by anti-Semitism and anti-Americanism.” Moynihan was “surprised he stumbled into this particular pack of UN trouble,” as he was not particularly concerned with Israel per se, but rather “he wanted to defend democracy and decency.”

On PBS’s Firing Line, Moynihan was pressed by the host, conservative intellectual William F. Buckley, on why he supports voting in the General Assembly. “I don’t on principle ever like to give up the right to vote or even the practice of voting,” Moynihan replied. He also argues that “the one thing those small countries have is a vote,” which he considers to be important as “the symbolic membership entitlement.”

Buckley, responding in a wordy analysis, suggested that it becomes “a greater act of paternalism — if you’d like a condescension — to vote and pay no attention to the result than to decline to vote on the grounds that, by not declining, you grant a solemnity to the process which you are not willing to accept the consequences of.” In other words, it seems more disrespectful, according to Buckley, for Moynihan to continue to participate in a process that he does not take seriously. If we are to be honest about fundamental problems at the UN, it may be best to hold off on voting.

Moynihan conceded that “I don’t know that I would profoundly disagree with that but I would say to you that we’re gonna go on voting — while I’m there I’m gonna go on voting — but I certainly am also gonna try to be part of an American delegation that speaks to the issues, speaks very seriously and says to the nations that listen, ‘we take your vote seriously…and will have to make our own judgments about the aftermath.’”

Ultimately, the “Zionism is racism” resolution was revoked by the General Assembly on December 16, 1991. The Times noted how, under the administration of President George H. W. Bush, “United States embassies around the world were instructed to put maximum pressure to secure the repeal.”

Many countries had switched their votes from the 1975 resolution, including even cosponsoring the repeal. Proponents of the revocation argued that the resolution was “out of date because it was a product of the cold war” and a push by the Soviet Union and allies as part of their mission of “attacking capitalism and propounding a new economic order,” the Times explained.

Moynihan’s tenure at the UN was short lived. The same cannot be said about the 24 years he served as senator from New York (1977-2001). Gil Troy notes that “Moynihan’s stand made him an instant political celebrity.” A 1982 Newsday piece profiling Moynihan describes how he was “a rousing orator and a compelling conversationalist.”

Known for his bipartisan activity, his obituary in the Times described Moynihan as “more a man of ideas than of legislation or partisan combat,” and “enough of a maverick with close Republican friends to be an occasional irritant to his Democratic party leaders.”

Moynihan’s speech, standing up to the General Assembly in a positive and inspiring oration in the midst of a dark moment for the United Nations and for Israel, is one remarkable event in the history of the continuing relationship between two true allies — the United States and Israel — that is worth remembering.