Last time I wrote about the historical precedent surrounding celebrating New Year’s during uncertain times. What I did not expect was that the year was not quite over for my family and me, and I was faced with the reminder that uncertainty is, of course, not just on the national or international level, but can be present in our individual lives as well.

On New Year’s Eve we planned to go to Long Island to help make a minyan for the burial of my aunt’s uncle, who had passed away unexpectedly. It was around 10:00 AM, and my father was revving up the car, ready to go.

Literally a minute before I went outside my mother received a phone call. Fern Horwitz, her mother and my grandmother, passed away.

I head outside to inform my father, who is still sitting in the car ready to go. As I am racing downstairs I think about numerous things. My mother being “an orphan.” What was going to happen in the next few minutes. How we were going to inform New Year’s Eve guests that the plans were off.

I signal my father to come back inside, and he sensed something was wrong. I tell him, and we head in. Thankfully, the aforementioned minyan was able to happen without us.

We certainly called often, specifically each Friday to say “good Shabbos.” In fact, while many would just call again another time, my phone is flooded with voicemails from her. But Grandma Fern was not regularly present in our family’s daily life because, sadly, she struggled with health issues and did not live nearby. Thankfully she was in the constant care of her amazing assistant Katie, who with her family would become very close friends with us.

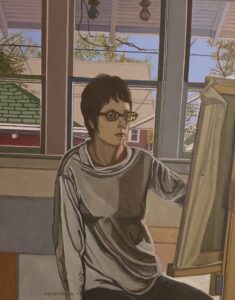

Prior to her decline in health, and even to a certain extent thereafter, Grandma Fern was a phenomenal artist, and her legacy — through her paintings — can be found everywhere in my house.

She had a keen eye for detail, and using her unique artistic mind she saw the angles, contours, and shadows in everyone and everything.

I highlighted in prior articles how the mediums of pictures and film can be wonderful for learning about the past, including one’s family history. What I had not yet explored was how art is another visual medium that can bring the past to life, and leave a legacy for subsequent generations. I come from a family of artists — Grandma Fern and her aunt and uncle were artists. As for me, I can draw a nice stick figure.

Indeed, art is the oldest means of visual depiction, and in its more modern form it is invaluable for the purposes of, among other things, historical record and preservation. Art allows us a realistic glimpse of historical people and events that preceded the photograph. Art is why we can put a face to the name of famous figures like William Shakespeare and George Washington.

In his 1940s book The Arts And The Art Of Criticism, Theodore Meyer Greene highlights another value in art when he asserts that the artist differs from the scientific thinker because the former “apprehends reality in terms of individuality and value, not in terms of abstract generality.” In other words, instead of just facts and figures without a particular meaning, artists bring interpretation of the world around us.

The artist’s goal, unlike the scientist, “is not the mere conceptual apprehension of truth for its own sake,” but it is philosophical as well, dealing with the “comprehension of reality in its relation to man as a normative and purposive agent.”

Greene continues, noting that art is not entirely philosophical either, differentiating itself from morality and religion because it is more universal, not focusing on activism or compelling believers. “It refrains, at its best, from every form of propaganda,” he argues.

Consider the famous painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware,” which depicts a dominant, confident leader, George Washington, standing in a boat as his men row across the Delaware River during the Revolutionary War.

Though it was created in 1851, many years after the actual event took place, we can learn a lot from this illustration, even setting aside its historical inaccuracies and unlikelihoods. For instance, Washington’s posture in the painting communicates his determination, even if he may not have literally stood in the boat.

What the case of “Washington Crossing the Delaware” can show is that, as a historical resource, art has the potential to evoke emotion and empathy with the subjects much better than mere words, while at the same time not necessarily promoting a specific agenda. That is why this medium can be so unique.

Perhaps most admired in my family is Grandma Fern’s self-portrait, over half a century old, which had an amazing amount of detail and use of color.

What seems to be reflective of her life is that Grandma Fern arguably appears older in this self-portrait than she actually was at the time — 28 years old. Grandpa Joel A”H, who was her husband at that time, reflected on how he felt that her eyes looked distant in this portrait, which may have signaled her troubles to come, including bouts with depression.

Grandma Fern’s life was dramatic in many respects, but one thing resonates with all of us, and makes us all very proud — including herself. And that is her talent and her passion for art, and what she produced through it.

Whether it is funny caricatures, recognizable portraits, or incredibly detailed scenes, Grandma Fern’s legacy of art has much to be ever more enjoyed, interpreted, and learned from for generations to come.