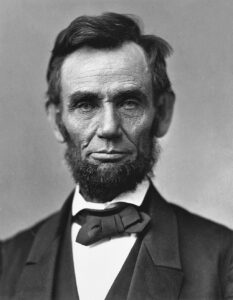

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln responded in a public letter to Horace Greeley’s editorial criticizing him in the New York Tribune. He made it very clear what his primary objective was during the Civil War: “I would save the Union.”

“My paramount object in this struggle,” Lincoln continued, “is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery.” Setting aside his personal revulsion of slavery, and his “wish that all men every where could be free,” his decision regarding the slaves would only be based on what he felt was the best option, towards the ultimate goal of restoring the Union.

“If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it,” he wrote. “And if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.”

Radical Republicans and abolitionists likely Greeley were pressuring Lincoln to abolish slavery. Yet on the other hand were people in the Union who sympathized with the perspective of slaveholders, as well as those in the “border states” who voted against Lincoln, had slaves, and yet still supported the Union. These two opposing attitudes within the Union camp were weighing on Lincoln as he pondered signing the Emancipation Proclamation, which would declare the slaves in Confederate states to be free.

I visited the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum recently, and remember entering an exhibit focused on Lincoln’s dilemma over the proclamation. One walking down the hall will hear loud voices on either side airing out their opinions — and talking points, if you will — surrounding slavery and the proclamation. The document goes too far for some. For others, not far enough. It is overwhelming, and clearly designed to overstimulate visitors and have us experience how Lincoln might have felt.

“Among the friends of the Union there is great diversity of sentiment and of policy in regard to slavery,” Lincoln observed in his annual message to Congress in 1862. “Some would perpetuate slavery; some would abolish it suddenly and without compensation; some would abolish it gradually and with compensation.”

Lincoln ultimately issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that effective January 1, 1863, “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

Through this act, he abandoned his previous approach of avoiding the issue of slavery directly and just focusing on restoring the Union — a philosophy which had appealed to the border states.

In a literary magazine article authored in 1880, a relatively short time after the Civil War, scholar James Welling analyzed Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation situation. It was “so warmly praised on the one hand, or so warmly denounced on the other,” he asserted. But now, with the war over but in recent memory, “the time has come when we can review this act of Mr. Lincoln’s in the calm light of reason.”

According to Welling, Lincoln saw the proclamation “as a political necessity,” and in turn a “military necessity,” since it would keep the radical abolitionists in check and bring greater unity to the fight against secession.

Lincoln’s reasoning here is important because, as he understood the law, such a proclamation can only be enacted with the “war powers” granted him as Commander in Chief for the purposes of furthering the Union’s military objective. That is why the aforementioned “border states,” who were not at war with the United States, were unaffected by this proclamation. Their slaves officially remained slaves until after the war.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a mostly symbolic move, but it dramatically changed the character of the war from one about preserving the Union to one that also included fighting for freedom.

Lincoln ultimately expressed how central the issue of slavery was in the Civil War, which is noteworthy considering his earlier, more open-ended message to Greeley. “Without slavery the rebellion could never have existed,” he said in his address to Congress. “Without slavery, it could not continue.”

Harold Holzer, a scholar of Lincoln, highlights Lincoln’s brilliance when it came to his handling of the discourse surrounding the proclamation. He expressed in the Greeley letter his wish to strictly do what is in the best interest of saving the Union. The impending proclamation was on Lincoln’s mind at the time, but he did not mention that in this public letter. Instead, he laid the groundwork for his decision to come.

“Lincoln’s presidential writing,” Holzer explains, had “uncanny success at changing hearts and minds through logic, not passion, and through powerful words alone, not personal appearances.” Holzer continues: “As Lincoln well knew when he wrote that letter, he had already determined to do just what he had told Greeley he had not yet decided on! The proclamation was already drafted.”

Lincoln was proud of the Emancipation Proclamation. Artist Francis Carpenter, whose painting depicted Lincoln and his cabinet reading the document, recalled to The New York Times how Lincoln told him “it is the central act of my administration.”

Being exempt from the proclamation did not stop Union supporters who opposed banning slavery from being agitated by this development. George McClellan, a Union general who was sympathetic to the viewpoint of slaveholders, was furious at the “infamous” proclamation. However, he eventually resolved to continue fighting on behalf of the Union.

According to Civil War historian James McPherson, McClellan went so far as to prevent his subordinates from even casually talking of insurrection. He also stated that “the remedy for political errors…is to be found in the action of the people at the polls.” McClellan would run an unsuccessful campaign for president against Lincoln in 1864.

Meanwhile, the Emancipation Proclamation was, unsurprisingly, met with vitriol by the Confederates. Jefferson Davis, who led the Confederacy, observed in a speech how “this measure possesses great significance.” He blasted Lincoln as being “utterly without constitutional power to do the act which he has just committed,” and asserted that this demonstrates the United States’s “inability to subjugate the South by force of arms.”

Welling, in his analysis, concluded that the Emancipation Proclamation was “extra-constitutional.” But he gives Lincoln some credit: “there is something worse than a breach of the Constitution. It is worse to lose the country for which the Constitution was made.”

It is quite noticeable how much discourse and controversy — whether it be legal, political, or moral — surrounded a decision that today, and to some extent even then, is morally clear: the abolition of slavery.

As we experience history being made in real time, it is interesting to reflect on ourselves and how our opinions and decisions, individually and collectively, might be judged several decades from now. Who is on the right side of history? And whose strong convictions will the passage of time essentially obliterate, as with those who defended the institution of slavery?