A plague has broken out, and everything is closing down. “Lord!,” someone remarks, “how sad a sight it is to see the streets empty of people.” This may sound like March of 2020, which is now three years ago this month, but I am actually referring to August of 1665. And the individual quoted is known diarist and member of the English parliament, Samuel Pepys, speaking of the bubonic plague in his diary.

Also during this time, Isaac Newton returned from Trinity College, which had closed because of the plague. At this point is when the familiar legend of the apple falling from the tree took place outside his family home, Woolsthorpe Manor. Reflecting on his accomplishments during that time, Newton is quoted as saying “all this was in the two plague years of 1665-1666. For in those days I was in the prime of my age for invention.”

It should be noted that biographer Richard Westfall, in his book Never at Rest, challenges the idea that this particular episode had a special impact: “If we focus our attention on the record of his studies, the plague and Woolsthorpe fade in importance in comparison to the continuity of his growth.”

But regardless, while the circumstances of the plague may not have actively contributed to Newton’s strides in his theory of gravity during that tragic and unusual time, it does show that he did not allow disruption of normal life to hinder his studies. His success was not thanks to the shutdowns, but in spite of them.

Similarly, Covid-19, as tragic as this pandemic was, forced many people to adapt to the digital age and try to continue our everyday lives as best as we can given the cards we have been dealt. As the shutdowns early on began, I regrettably figured that because of the age of one particular professor of mine, he would have a harder time adjusting to these strange circumstances and conducting class online. To my surprise, he was the first of my professors to resume teaching, and it was through his class that I was introduced to a new platform: Zoom.

When I began homeschooling for high school in 2015 I remember thinking that remote learning would become more mainstream in 10 years. So it happens that online classes are no longer just for less conventional circumstances or select universities. It is now recognized as a standard way one may conduct their studies.

The same happened in other aspects of one’s life, with the remote option sufficing for work or even spending time with family and friends. Nobody would have

expected it to happen this way however. This public health crisis essentially forced us into the future — reliance on virtual resources surged exponentially in such a short period of time.

To be sure, some things are simply better in person. But with the technological skills and discoveries we made while trying to handle the difficulties of quarantine, we arguably came out of the pandemic smarter, more flexible, and with the benefit of more options as we realize how much can be done remotely. The inconvenience of being forced to do things online brought about the convenience of being able to do things online that we otherwise may not have deemed practical.

As historic a time this was, it seems hardly without precedent. We see from the example of previous outbreaks and quarantines not only similar instances of drastic measures, isolation, and tragedy, but our ability to reconcile with these challenges and try to make the best of it.

With the Great War coming to an end in 1918, the world faced yet another challenge: the Spanish Influenza, which killed hundreds of thousands of Americans and prompted measures against the spread of the disease.

The New York Times in October of 1918 quoted the Surgeon General of the United States Rupert Blue, who said that “those having the proper authority” should “close all public gathering places if their community is threatened with the epidemic.” New York City Health Commissioner Royal Copeland acted shortly thereafter, finding the subway rush hour to be a significant cause of transmission. So he ordered changes in business opening and closing hours, therefore “distributing the travelers over a greater space of time,” as the paper put it.

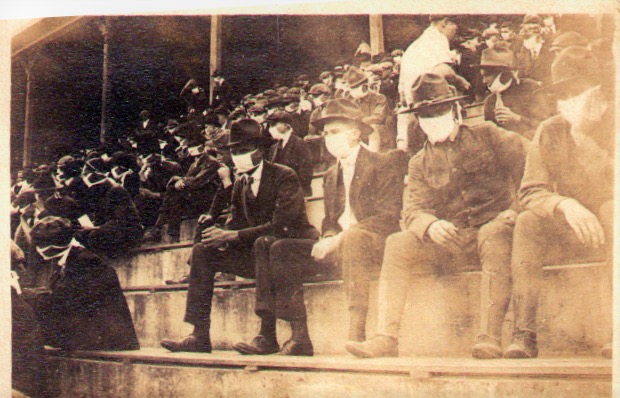

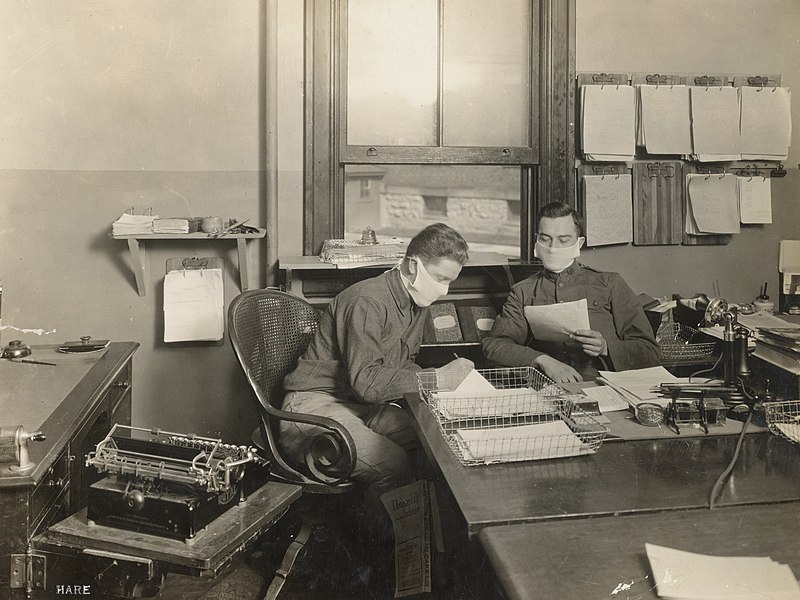

A few days later the Times reported that the National Association of Motion Picture Industries voted “to discontinue all motion picture releases after October 15, until the epidemic had abated.” The Atlanta Constitution noted how Chicago prohibited nonessential public gatherings. In San Francisco, a mask mandate was put into place. “With the exception of necessary time at meals, masks must be worn continuously,” reported the San Francisco Chronicle.

The effectiveness of certain measures was not unanimously agreed upon, however. An article in the Times highlighted in December of 1918 the different ways health officials disagreed. “Health Officers from the Southeast…favored strict quarantine measures, and those from smaller cities were moderately favorable to quarantines and the use of masks.” In the “larger cities,” however, officials “opposed both these measures and placed great reliance on vaccine.”

Rewind over a hundred years. Historian Julie Miller of the Library of Congress details in a 2020 article the 1793 epidemic of Yellow Fever in the newly formed United States, which ravaged Philadelphia and killed around 5,000, or about 10% of the city. Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of State at the time, wrote how “the week before last the deaths were about 40. The last week about 80. And this week I think they will be 200. And it goes on spreading.”

Philadelphia is “now almost depopulated by removals & deaths,” President George Washington wrote. Because of Yellow Fever, he and his cabinet, including Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton, fled to Germantown in Philadelphia and operated from there.

As we look back on the beginnings of the pandemic, just maybe some may find reassurance in seeing how this unique situation we encountered beginning three years ago this month, a deadly and contagious virus, does have some precedence. Legendary historical figures like George Washington and Isaac Newton had to deal with these kinds of circumstances too, yet they worked around the challenges they faced. And so did we.