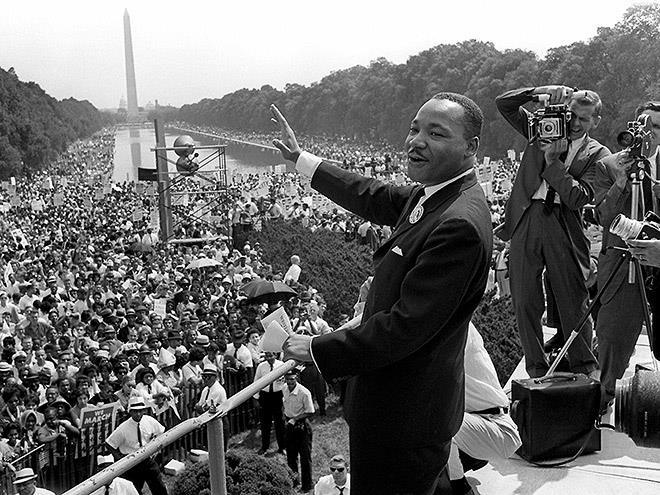

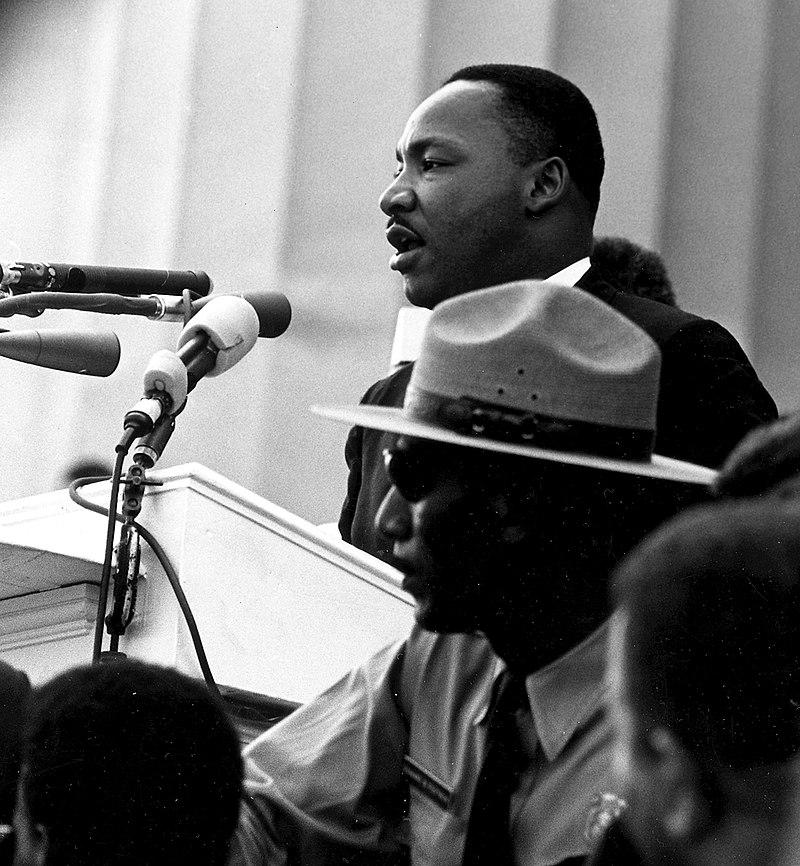

With the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington coming up on August 28, we are once again reminded of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and his dream that one day people “will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

This quote is often highlighted by those who seek to promote “color blindness” and thus challenge race-based policies such as reparations or affirmative action, which aim to boost disadvantaged minorities. But a broader look into King’s statements and actions demonstrates that he was not necessarily color blind.

Some of King’s proposals did indeed include what we might call “color blind” policy. After all, why not promote programs that address racial inequities while simultaneously helping all people?

In his 1964 book Why We Can’t Wait, King pushed for a “Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged,” which would ultimately help all poor people, whether black or white, as King references disadvantaged white people as having been “derivative victims of slavery” who continue to suffer under poverty too.

But King had rooted that program on the basis that Black people are deserving of “compensatory or preferential treatment,” comparing Black “equality” to one man entering the starting line of a race 300 years after another man. This is the philosophy of proponents of color conscious considerations, such as with affirmative action or reparations.

To demonstrate this, King directed us to his discussion with Indian Prime Minister Nehru about the “untouchables,” whose situation he describes as “not unrelated to” Black Americans. It became outlawed to discriminate against the untouchables, but the Indian government sought to do even more — to help them.

“Moreover,” King writes, “the Prime Minister said, if two applicants compete for entrance into a college or university, one of the applicants being an untouchable and the other of high caste, the school is required to accept the untouchable. Professor Lawrence Reddick, who was with me during the interview, asked: ‘But isn’t that discrimination?’ ‘Well, it may be,’ the Prime Minister answered. ‘But this is our way of atoning for the centuries of injustices we have inflicted upon these people.’”

Reflecting on this scenario, King stated that “America must seek its own ways of atoning for the injustices she has inflicted.” He clarified that atonement should not be for its own sake, but rather a “moral and practical” solution.

So, it seems that King agreed with the principles behind race conscious initiatives, and noted in a positive light similar efforts as they were happening in India. His actions also reflected this.

King was behind Operation Breadbasket. Under this program, clergymen would inquire about the number of Black employees a business has, before providing recommendations based on population data on how many jobs should be requested.

In his 1967 book Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community, King explains that logic would dictate if a city were to have a population that is 30 percent Black, then Black people “should have at least 30 percent of the jobs in any particular company, and jobs in all categories rather than only in menial areas, as the case almost always happens to be.”

If negotiations surrounding hiring or job upgrades fail, “the step of real power and pressure is taken,” King states. Among other things, this would include “a massive call for economic withdrawal from the company’s product and accompanying demonstrations if necessary.”

In addition to this, he requested that establishments in Black communities would sell Black-owned products and deposit their income in Black-owned banks.

In a conversation with the Rabbinical Assembly just ten days before his assassination, he embraced Operation Breadbasket as “one of the best programs we have,” indicating his likely approval of the philosophy behind modern affirmative action.

Again, King was very much an advocate for class-based action and policy too. But he warned against allowing a principle of “color blindness” to hinder the goal of Black equality.

For instance, discussing the issue of education, he wrote that “the task is considerable” — it is not only about bringing Black students into higher levels of education, but “to close the gap between their educational levels and those of whites.” He further goes on to note that otherwise, as Black Americans excel in education, “whites will be moving ahead even more rapidly.”

Likewise with the ultimate goal of integration. King told the Rabbinical Assembly that “separatism as a goal,” is, of course, negative and unrealistic. But there was a common and misguided conception of integration, he argued, “and it ended up as merely adding color to a still predominantly white power structure.” Integration should be seen in “political terms,” King said: “there are points at which I see the necessity for temporary segregation in order to get to the integrated society.”

King described a task that is “on two levels:” “we must constantly work toward the goal of a truly integrated society while at the same time we enrich the ghetto.” Ultimately, this “will make it possible to disperse it at a greater rate a few years from now.”

While King suggested alternatives to the term “Black Power” such as “black consciousness” or “Power for Poor People,” he made it clear that Black people should “work passionately for group identity. This does not mean group isolation or group exclusivity. It means the kind of group consciousness” needed “to participate more meaningfully at all levels of the life of our nation.”

We can see that both in political theory and in practice King’s nuanced and multidimensional approach to pursuing equality was not color blind, but rather color conscious, in order to counteract racism and its lasting effects. As such, he very well may have been open to race conscious programs like reparations and affirmative action too.

In 1996, California voters approved Proposition 209, eliminating affirmative action “to the extent these programs involve ‘preferential treatment’ based on race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin.”

Civil rights activist Coretta Scott King wrote an article in The New York Times stating that supporters of the proposition to ban it “distorted” her husband’s words: “My husband unequivocally supported such programs. He did indeed dream of a day when his children would be judged by the content of their character, instead of the color of their skin. But he often said that programs and reforms were needed to hasten the day when his dream of genuine equality of opportunity — reflected in reality, not just theory — would be fulfilled.”

“Like my husband,” she wrote, “I strongly believe that affirmative action has merit, not only for promoting justice, but also for healing and unifying society.”