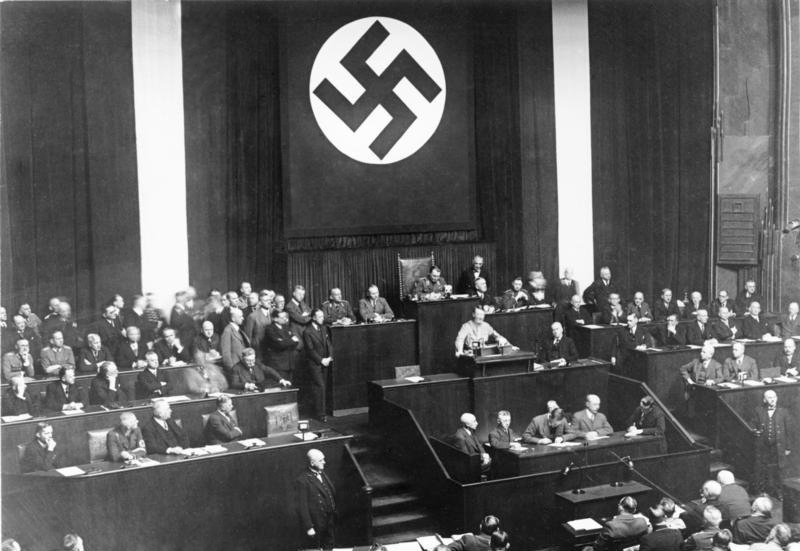

March 23, 1933. The German parliament, known as the Reichstag, is meeting at the Kroll Opera House instead of the usual building which was damaged by arson about a month earlier. Members of parliament are preparing to pass the Enabling Act — the law would effectively make Hitler dictator.

The Communists were banned, and they alongside many Social Democrats were imprisoned or hiding. Historian Richard J. Evans details how one member of parliament, Wilhelm Hoegner, a Social Democrat who would join his party in voting against the act, found the environment to be intimidating for those who were not Nazis. “Young lads with the swastika on their chests looked us cheekily up and down, virtually barring the way for us. They quite made us run the gauntlet, and shouted insults at us like ‘centrist pig,’ ‘Marxist sow.’” Armed guards were present inside. A massive Nazi flag hovered above the stage.

The devastating Enabling Act is about to be passed with an overwhelming majority surpassing the ⅔ requirement. Hitler gave what was his first speech before parliament, making the case to pass the act, especially trying to appease the somewhat undecided Catholic Center Party whose support was needed. During the break after Hitler’s speech, they made it clear that they would vote yes.

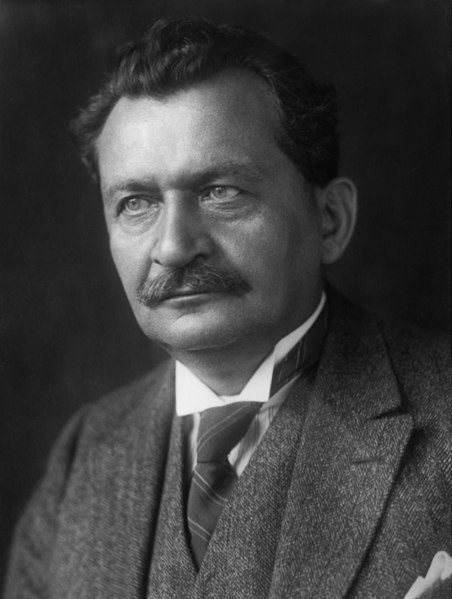

Once parliament came back into session, one member of the Reichstag stepped up to give the only speech in opposition to the Enabling Act. Speaking to “the persecuted and the oppressed” he said that “your steadfastness and loyalty deserve admiration. The courage of your convictions and your unbroken optimism guarantee a brighter future.” These are the final words spoken at the podium by Chairman Otto Wels of the Social Democratic Party, as he rebukes Nazism and this act despite the obvious fact that it was about to pass.

Facing laughter from the Nazis and support from fellow Social Democrats, Wels’s words essentially marked the downfall of the democratic Weimar Republic and the tragic rise of the Third Reich. He and fellow Social Democrats who were not yet thrown in jail were united in opposition to the Enabling Act, all voting against it, but were overwhelmed by the supermajority consisting of the Nazis and coalition parties.

Earlier in his speech, Wels also rejected the use of the word “socialist” in the official title of the Nazi party: the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. He said that “the relationship of their revolution to socialism has been limited to the attempt to destroy the Social Democratic movement, which for more than two generations has been the bearer of socialist ideas and will remain so.” Had they truly wanted socialist policies, he continued, “they would not need an Enabling law.” He also pointed out that, given the clear majority the Nazis assembled, there was no reason to pass this act. “Freedom and life can be taken from us, but not our honor,” he declared.

Wels was born on September 15, 1873 in Berlin, and according to historian William Smaldone he had an active childhood and was immersed in socialist politics at an early age. He worked as an upholsterer, had traditional values, and was ambitious. In November of 1918 he became Military Commander of Berlin, and took on the task of restoring order amidst far-left labor uprisings that were taking place. When he tried to negotiate with a group of protesters from the marines who wanted more pay, he was captured and beaten before being rescued. On December 27 he resigned as commander, and in 1919 he became Chairman of the Social Democratic Party. He was an effective leader and saw a lot of success for his party until Hitler’s rise to power.

Wels went into exile in 1933, but continued operating as chairman as he lived in Prague. He then moved to Paris in 1938, where he would pass away on September 16, 1939, just over two weeks after Germany’s invasion of Poland and the beginning of World War II.

Hitler was present during Wels’s speech, and historian Frank McDonough describes how he was “rattled” by how excellent it was, reportedly taking notes throughout. Afterwards, Hitler gave a fiery rebuke: “You are no longer needed,” he declared. “The star of Germany will rise and yours will sink. Your death knell has sounded.” A thunderous applause ensued.

Wels had a unique opportunity that day: he directly faced and chastised the most evil person in history, being the sole voice of divergence in the Reichstag to take the stage. Smaldone observes that Wels “literally risked his life” to deliver those remarks. According to Evans, he even had cyanide ready in his pocket in case he would be captured and tortured afterwards. Former chancellor Heinrich Bruning, who played a role in Hitler’s rise to power, recalled that Wels was Germany’s “bravest man in the fight against Hitler.”

Now, as admirable as Wels and his speech may be, things were not so simple. For example, it would seem obvious German Jews would have voted for the Social Democratic party, considering that they were the only ones to ultimately oppose the Enabling Act. The party was home to several prominent Jewish politicians too. However, as the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported after the general elections of March 5, 1933, “only a minority of Jews supported” the Social Democrats and therefore were in a position “of the utmost difficulty,” being “compelled to vote for a party which may ultimately enter a coalition government with Hitler.”

Many supported the German State Party, which was the result of a merger between the German Democratic Party (popular among German Jews) and the People’s National Reich Association. Others settled on supporting the Center Party and even the far-right German National Party. Unfortunately, all these parties would end up voting for the Enabling Act — that is, except for the Social Democrats.

Another issue is how Wels and Social Democrats responded to Nazism. Shirer observed that Social Democrats “bore a heavy responsibility for the weakening of the Republic.” For better or worse in countering Nazism, Wels opposed strategies like employing a new party symbol or engaging in propaganda — methods that the Nazis were using. According to Smaldone, when an idea was brought to the table involving new symbols and campaign posters to bring more enthusiasm to the Social Democratic movement, Wels said “we shall make ourselves look ridiculous with all this nonsense.” He was fiercely opposed to extremists, including both Fascists and Communists, and could even have appeared soft with the more moderate avenue he took to combat Nazism, including avoiding violent resistance which he maintained would have made things worse for their cause.

Just a couple of months after his speech against the Enabling Act, Wels would go into exile in Prague, continuing to rebuke Hitler and Nazism. Regardless of how Wels may have felt about diversity itself, he saw right through Nazi scapegoating and lies. In a statement to the New York Times he said that “whom in the whole world can Hitler persuade that it was necessary to…expel Einstein…engineer the persecution of the Jews…suppress all political parties” and “muzzle the press?” He continues: “to be against Hitler means to be for the German people.”

Wels was himself also a direct target of the Nazis. On April 23, 1932, 11 months to the day before the passage of the Enabling Act, Wels and Otto Bauknecht, another socialist, were assaulted by a mob of Nazis led by Reichstag member Robert Ley. In January 1934, after Wels went into exile, the San Bernardino Sun reported that his property was taken by the secret police. In September of 1933, it was reported that a club in London for Nazis had posted photographs of prominent Germans with a notice: “If you meet one of them kill him.” Otto Wels was one of those listed.

Wels would stand against the Hitler regime for the rest of his life. In early September of 1939, less than two weeks before he passed away, Wels and Hans Vogel, another chairman of the Social Democratic Party, sent what newspapers called a “manifesto” to the German people, just after the invasion of Poland. “Get rid of Hitler,” it said. They proudly declared themselves “haters of the war dictatorship,” and urged that Hitler be overthrown in order to bring peace and order to Europe again.

To the very end of the democratic Weimar Republic the evils of the Nazi party saw a strong and significant, albeit tragically not sufficient, fraction of parliament oppose them, which is exemplified by Otto Wels and his historic speech against the decisive and destructive Enabling Act of 1933, making him a compelling voice in history we should seek to remember.